This post belongs to a series of three lectures "Changes and current challenges in Public Administration: a focus on the shifts in management modes of public service organizations, value generation logics of public service delivery, and performance management applied to governance"

This lecture focuses on the attempt to move towards greater recognition of the distinctive features of public policy management and governance.

Introduction

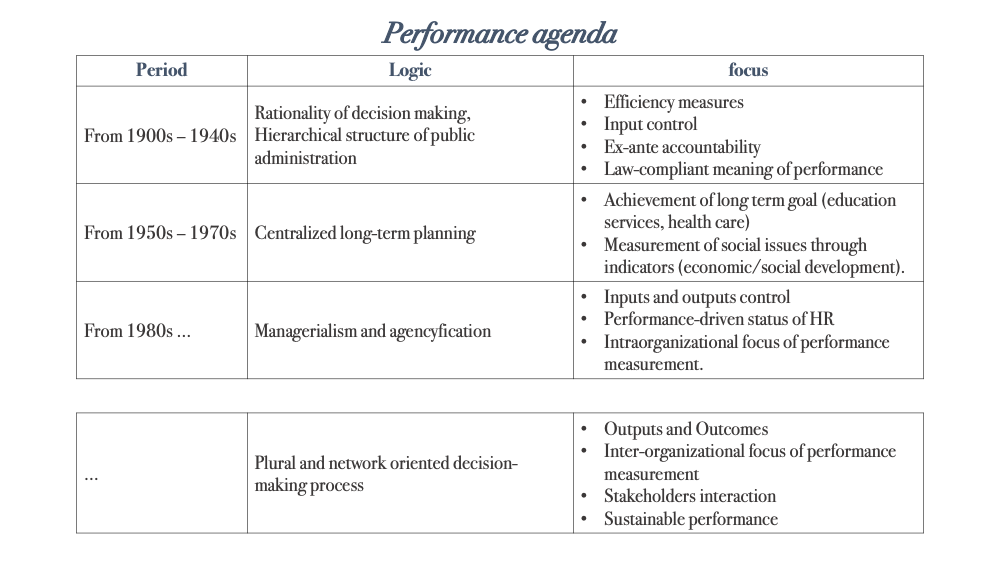

Performance ideas have been around for a hundred years or more. Wilson suggested in The Study of Administration in 1887 the “Politics-Administration Dichotomy”, which argues that public administration should not be influenced by politics. The main concerns of public administration at that time was increasing the efficiency of implementing public policies, which implies to measure how governments achieve public goals efficiently. Since then, the commitment of public sector organizations towards the management of their achievement has been increasing. However, the plural nature of public governance entails to shift from performance management to performance governance.

Before exploring how and why to span the boundaries of Performance Management from single organization towards an interinstitutional perspective, it is needed to gain an historical perspective on performance management. This implies to have a long-term perspective on the trend that has supported the spread of performance as main concern for public sector organizations. This particularly has occurred during the twentieth and twenty-first century (Van Dooren, 2008)

Research in public administration has clustered those movement that have contributed to the spread of performance management in three main periods:

- Pre-World War II (Old Public Administration).

- From the 1950s to the 1970s (the raise of the welfare state).

- From the 1980s onwards (New Public Management and Public Governance).

Before the World War II, the debate was characterized by two main arguments: rationality of decision making and hierarchical structure of public administration. These two principles found a synthesis in the “one best way”, meant as the existence of a standard. In fact, main authors that have shaped the model during this time were Max Weber and Frederick Taylor. The focus of performance management was on efficiency measures, input controls and ex-ante accountability (Bouckaert & Halligan, 2008a; Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2011).

From the 1950s to the 1970s, a second generation of performance movements promoted changes in the practice of performance management. In this case, the planning process was at the core of such initiatives: budgeting system, Management by objectives, and zero-based budgeting were used as method to make the best allocation of resources compared with long-term goal. In this context, the need of indicators emerged with the intent to measure and turn the focus of public policies on social issues, which further caused the raise of the welfare state.

From the 1980s onwards, fiscal crises and the ascent of new right movements (Thatcher and Reagan) promoted cutbacks on the welfare state. As a consequence, the development of managerialism in the 1980s resulted in a diffuse set of management reforms that spread globally in the 1990s and became known as the New Public Management (NPM) (Van Dooren, Bouckaert, & Halligan, 2015). According to this view, the public sector should consider a small policy board committed to policy design and the implementation organizationally separated from this and driven by performance-based logics. New public management made measurement gradually more extensive, more intensive and more external, than it was before. It had an orientation towards inputs and outputs control as source of accountability, together with and intraorganizational focus of performance measurement.

From an historical perspective the term performance refers to an agenda for both scholars and practitioners. Ongoing debate in performance studies is associated with the complexity characterizing policy making and implementation in the context of governance (Christensen & Lægreid, 2010; Halligan, 2010). The aim of such studies is to characterize performance management as method for implementing public governance. The roots of performance agenda in the public sector are not only associated with NPM and post-NPM studies, since the concept performance includes other arguments such as “establishing the rule of law, eradicating corruption, safeguarding equity, transparency and democratization” (Van Dooren et al., 2015) which are long-standing issues for public administration.

Changes and innovation in performance management theory mirror the paradigm shifts in the management mode of public sector organization (Osborne, 2006) and they includes different disciplines such as public administration, organizational studies, and strategic planning (Van Helden, Johnsen, & Vakkuri, 2012). The focus of performance management has turned from rules, inputs control, and compliance with regulations, as it was under the old classic paradigm of public administration, to outputs and efficiency, with the NPM, and finally to outcomes and effectiveness, with the spread of Public Governance (Imperial, 2005). During the age of NPM, the pressure was to improve efficiency and effectiveness of public agencies by making their management similar to the private organizations. However, there was a failure, since the attempts neglected the specific complexity of the public domain. For instance, cash flows can be used by firms to assess performance, at least from a financial perspective. For public sector agencies such as a university or a hospital, even when a single measure captures the volume of service provided to its users (e.g., the number of clinical treatments, or hours of lectures provided to students) it is not enough to understand the outcome of that delivery, though valuable. Despite similarities between private and public organizations the content of performance and its management system need to consider a multidimensional and balanced approach (Cepiku, 2016).

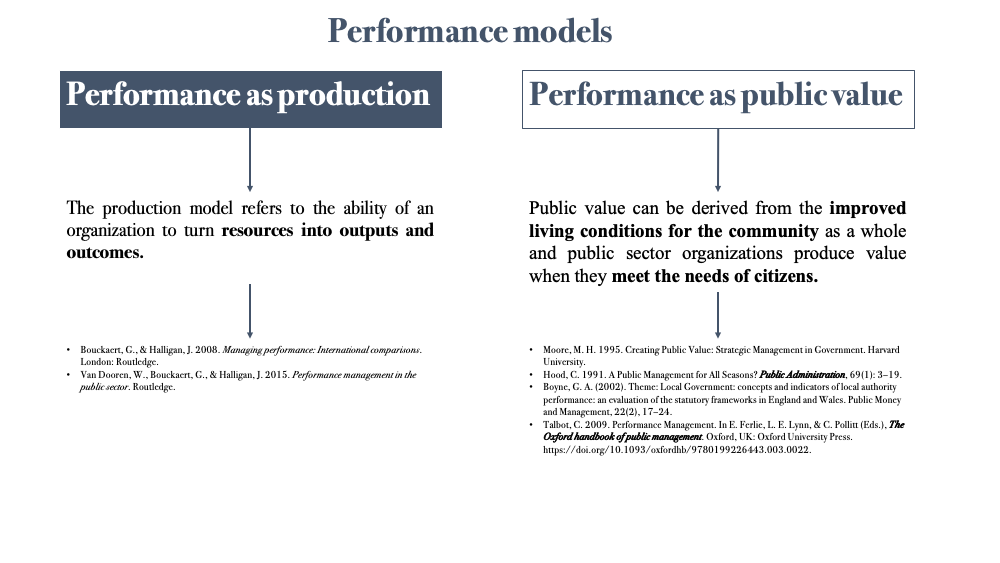

Two main approaches have defined performance. They can be labeled as the production model and the public value perspective.

Performance models

Performance is a multidimensional concept. Traditionally, performance has been framed through the “3Es” model (i.e., economy, efficiency, effectiveness) and of the “IOO” model (i.e., input, output, outcome) (Boyne, 2002). Although, a variety of models exist, performance is meant as a production, or alternatively as a public value.

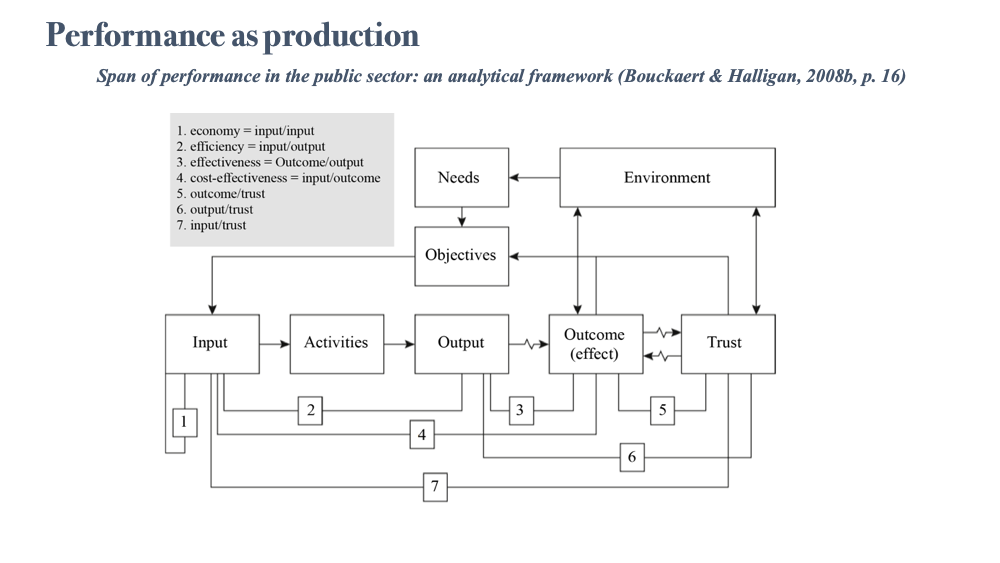

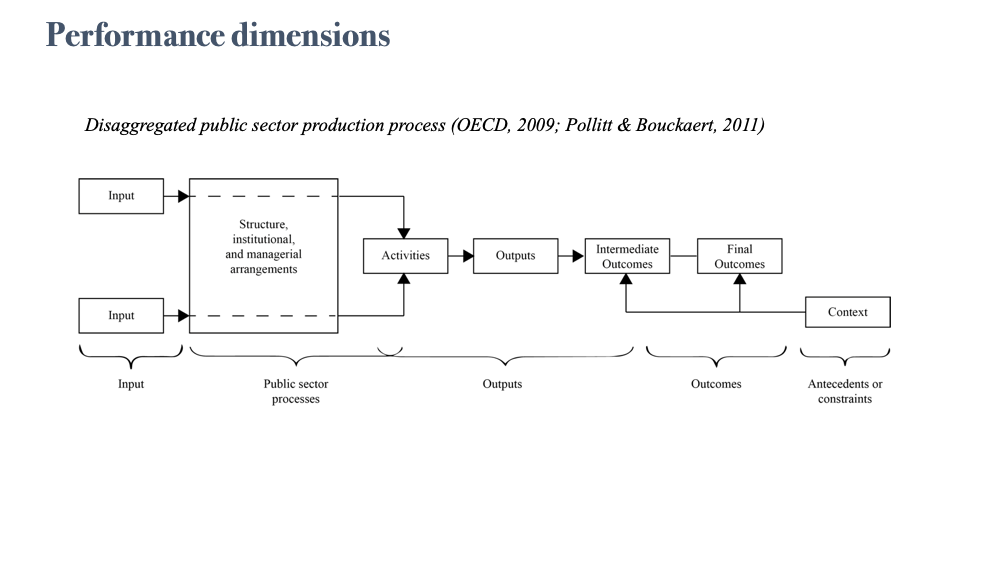

The production model refers to the ability of an organization to turn resources into outputs and outcomes, and it can be applied to an institution/organization and even to a policy program. According to the production logic, performance is meant as the quantity of outputs and related effects resulting from the exploitation of a quantity of inputs. Building on this concept, Pollitt and Bouckaert (2011) extended the standard model into a more comprehensive framework.

As the figure portrays, the analytical framework of performance – developed by (Bouckaert & Halligan, 2008a: 16) – widens “the span of performance” in the public sector and can be used to measure and manage both operational and process results (Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2011).

In line with the production logic, the analytical framework can support managers in measuring the economy, the efficiency, and the effectiveness of an agency or of a policy program. These three traditional dimensions can be associated to input indicators (input/input), to efficiency measures (input/output), and, eventually, to effectiveness indicators (outcome/output). In other words, organizations can measure the resources deployed (link 1), the efficiency in using them and the volume of output (link 2), the impact of such quantity (link 3), and cost-effectiveness relations, the quantity of input used to achieve such an outcome (link 4).

Outcomes are strictly associated with the trust. Central to the framework is the concept of trust, which is intended at an individual level (i.e., toward the person at the desk) and the level of an organization. Trust has consequence on citizen’s satisfaction (Bouckaert, Van de Walle, & Kampen, 2005; Van de Walle, Van Roosbroek, & Bouckaert, 2008) and it can also drive citizens’ engagement to public services provision (Osborne, 2018). Therefore, the relative level of trust between a public organization and the members of a community – and vice versa – impacts on effectiveness both output and outcome.

Besides traditional measures, the analytical model enlarges the scope of performance measures in public sector organizations, offering to managers and policy-makers a wider view of results. Particularly, it adds multiple dimensions, so to implement deeper performance appraisals at both organizational and intra-organizational level (i.e., the performance of a specific unit). To grasp the capacity of an organization to address socio-economic issues and reduce the needs of a community, the model compares the outcomes with the trust towards the organization. With the ratio between the output and the trust towards the organization, the model aims at capturing the ability of an agency, or one of its sub-unit, to deliver effective services to users and community. Lastly, by relating input to trust, it proposes to gauge the cost of citizens satisfaction for the organization. A group of trust indicators may support managers in capturing the ability of an organization to build consent around organization’s policies and decision rules by relating such a concept with outcomes (link 5), outputs (link 6), and input (link 7).

A starting point of the model are those societal needs of the environment based on which a public organization endows its system with the requested resources to deliver planned outputs. The latter are the services and products such as the number of authorizations issued by a Municipality, educational services, meals provided to students at a school canteen, surgery treatments, and vaccination treatments delivered to the community. These outputs are likely to produce outcomes. For instance:

- the time it takes for the municipality to issue an authorization may, in turn, impact on the prospected profitability of a business venture;

- the quality of academic educational systems determines the fraction of students finding a job after graduation;

- the post treatment cares and follow-up impact on the fraction of living patients after three years of a high-risky surgery treatment.

These examples of outcomes show that a policy program or a service has an ultimate impact on both the system and users, and how such a performance is tightly-coupled with specific public ends and nurtures the trust towards the organization. The extended production model connects both traditional measures of performance (economy, efficiency, and effectiveness) with trust measures. Additionally, it is not limited to an internal view of effectiveness, meant as a set of organizational results, but it crosses the boundaries of the organization and includes external and long-term dimensions of effectiveness (outcomes and trust).

A second approach to explore the content of performance can be associated with the studies on Public Value (Moore, 1995, 2013; Moore & Hartley, 2008). This perspective clarifies the substance (Van Dooren et al., 2015) of performance. Dubnick (2005) proposed four types of performance with the purpose to identify the material aspects of the tenet. He scored four types of performance along two dimensions, the quality of actions and the quality of achievements (Dubnick, 2005: 392)

According to his model, a first basic form of performance focuses on tasks execution; a second relates to competences, skills, and the knowledge incorporated into the execution of tasks. While the third type of performance relates to what is produced, namely the result of the process, the fourth is linked to the process itself. These four types of performance may be considered as typically applied to the concept in the existing literature (Dubnick, 2005: 394).

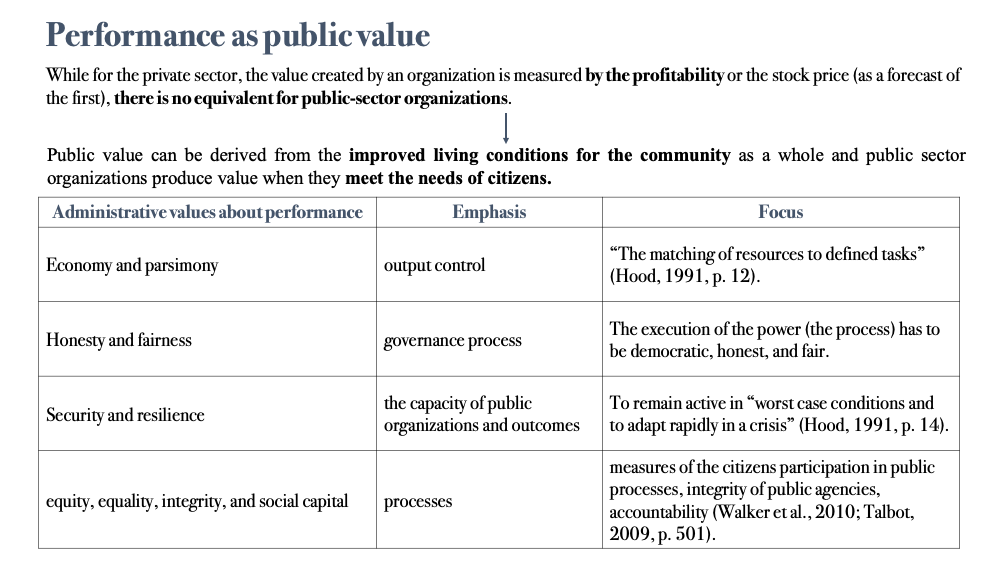

With the aim to operationalize the content of performance, Moore (1995, p. 10) asked himself what is meant as value into the public domain. While for the private sector, the value created by an organization is measured by the profitability or the stock price (as a forecast of the first), there is no equivalent for public-sector organizations. It should represent the ability of a public organization “to create value in the short and long run” or what Moore called the managerial success. Public value can be derived from the improved living conditions for the community as a whole and public sector organizations produce value when they meet the needs of citizens. Public value embraces several disciplines and it enhances the production model of performance (Voets, Van Dooren, & De Rynck, 2008). To this end, literature refers to the administrative arguments as grouped by Hood (1991). He clustered administrative values about performance in three groups:

- economy and parsimony;

- honesty and fairness;

- security and resilience.

The first group of values emphasizes output control since they are connected with “the matching of resources to defined tasks” (Hood, 1991: 12). The second cluster of value is associated with the governance process, since a government has to operate in a democratic, honest, fairness way. This group of values focuses on the process rather than on the results as claimed by the production view of performance (Voets et al., 2008). The third group – labelled as “regime” – includes values relate to resilience, endurance, robustness, survival, and adaptivity. This argument indicates the capacity of a public organization to remain active in “worst case conditions and to adapt rapidly in a crisis” (Hood, 1991: 14). The public value perspective of performance offers a framework which strengthen public governance, with additional dimensions (Boyne, 2002) including measures of the citizens participation in public processes, integrity of public agencies, accountability (Walker et al., 2010), and democratic values “like equity, equality, probity, and social capital” (Talbot, 2009: 501).

Performance Management

Performance is about results, but differs from a mere behavior since it includes some degree of intent (Dubnick, 2005). It can be conceptualized as “a set of information about achievements of varying significance to different stakeholders” (Bovaird, 2008: 185) and can be individual or organizational.

Components of performance management

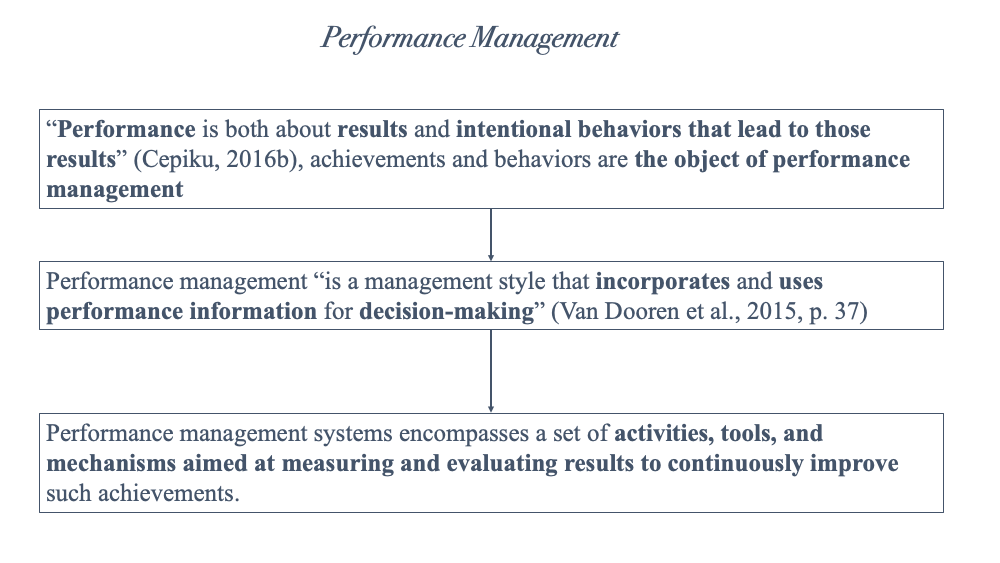

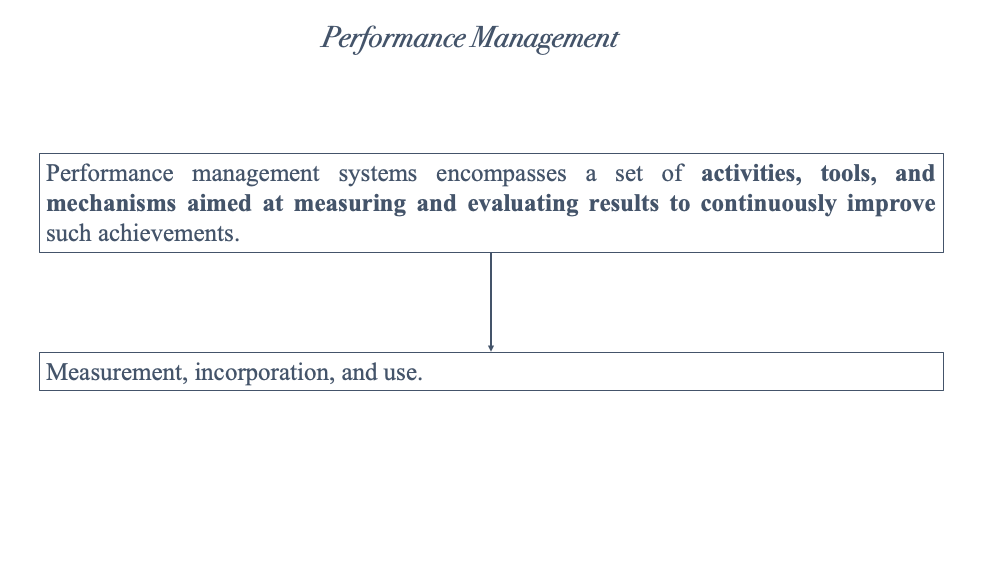

Performance is both about results and intentional behaviors that lead to those results” (Cepiku, 2016), achievements and behaviors are the object of performance management. It “is a management style that incorporates and uses performance information for decision-making” (Van Dooren et al., 2015: 37). Performance management systems encompasses a set of activities, tools, and mechanisms aimed at measuring and evaluating results to continuously improve such achievements. Performance management has been extensively adopted by public sector organizations and has produced a considerably body of knowledge (Bouckaert & Halligan, 2008a; Boyne, Meier, O’Toole, & Walker, 2006; Moynihan, 2008; Talbot, 2009; Van Dooren et al., 2015).

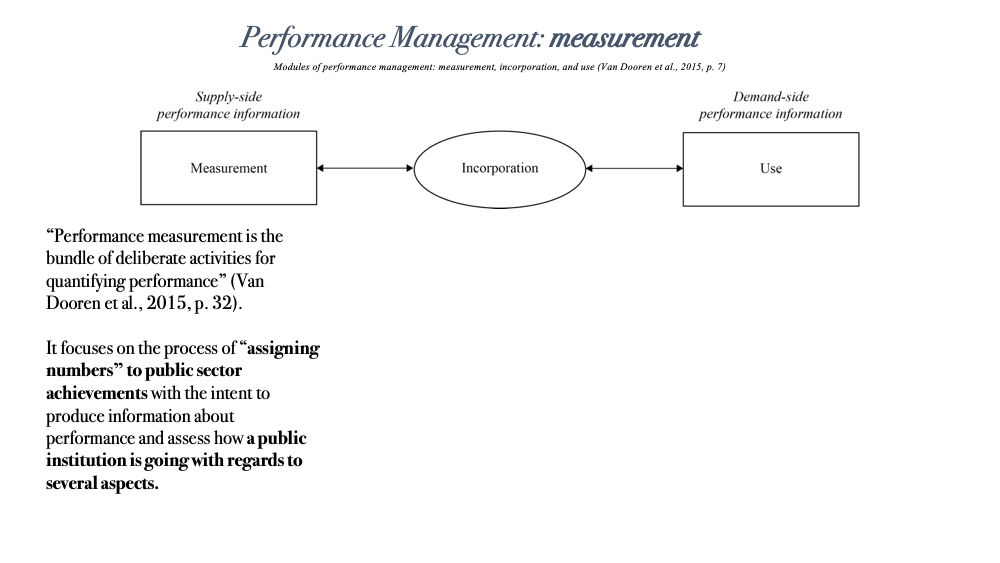

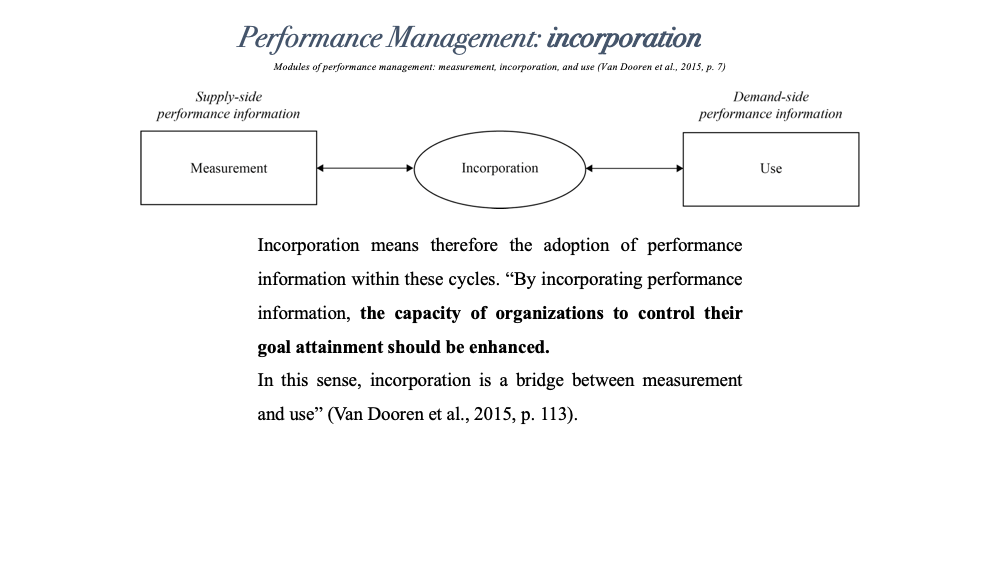

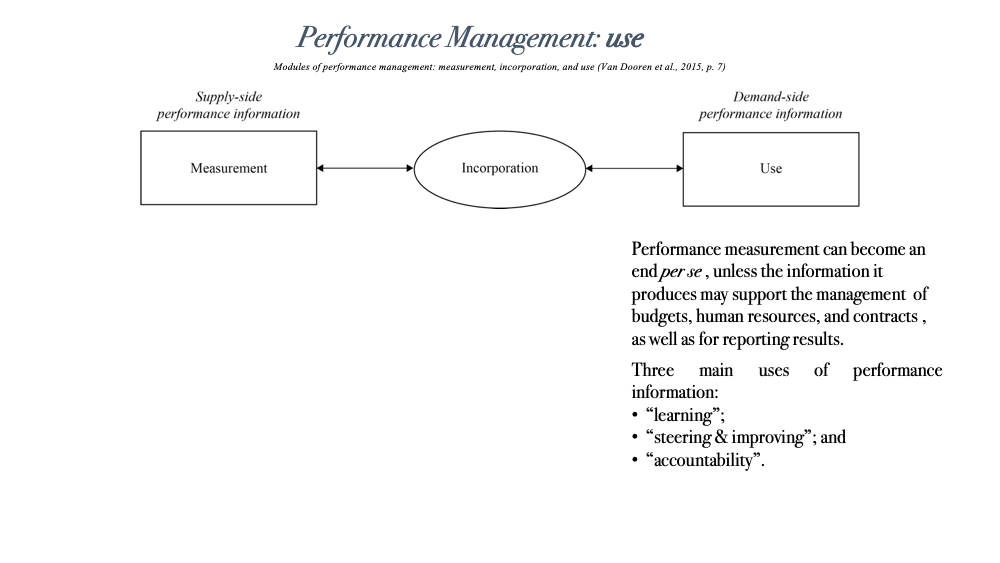

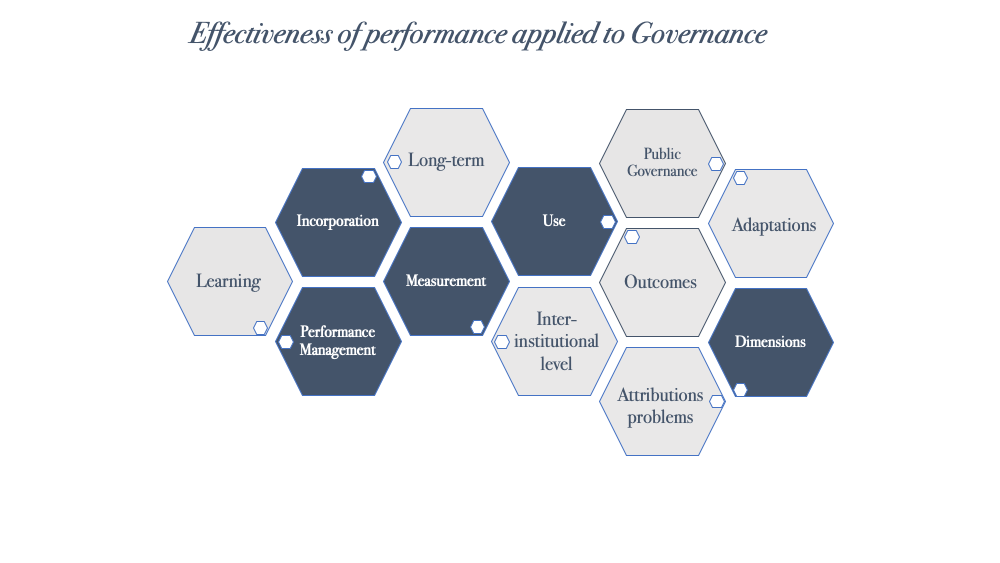

Performance managements includes tree modules. They are: measurement, incorporation, and use (Bouckaert & Halligan, 2008a: 215). These three modules compose a system whenever there is a procedure to account observations at different levels, and analyze them into management reports made available for different levels along the organizational structure (i.e., the incorporation), and finally the use of these for specific needs.

Performance Measurement

“Performance measurement is the bundle of deliberate activities for quantifying performance” (Van Dooren et al., 2015: 32). It focuses on the process of “assigning numbers” to public sector achievements with the intent to produce information about performance and assess how a public institution is going with regards to several aspects.

The first problem about performance measurement is to decide what to measure. To this end, different models (Balanced Scorecard, Common Assessment Framework, European Foundation for Quality Management model, ISO model) may adopted to understand different dimensions of good management and good governance (Bovaird & Löffler, 2003). In this sense, a public administration has to define to object of measurement (e.g., an organizational unit, internal focus, and/or measures for policy/service, external focus) and relate these measures to what information is needed and its purpose.

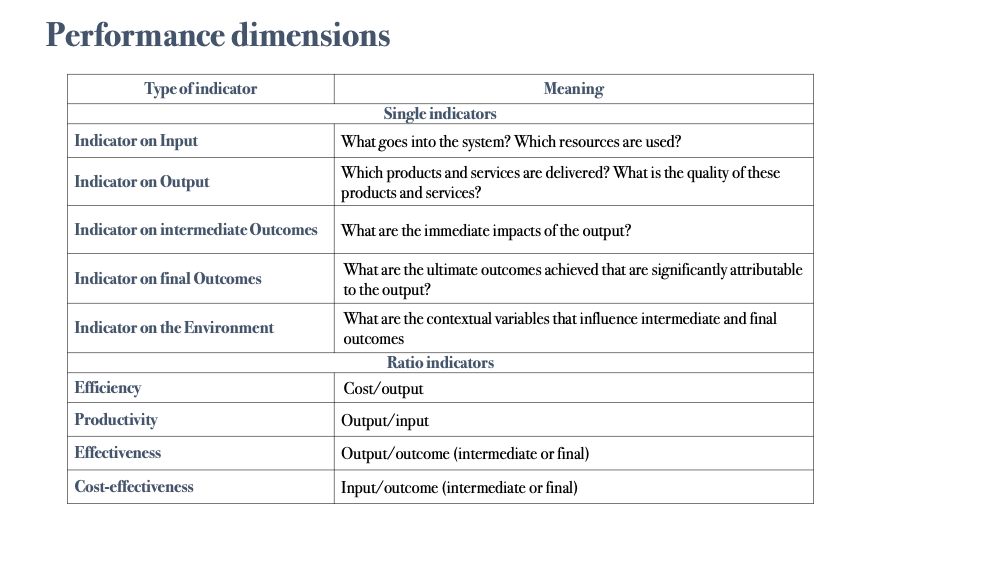

Measurement requires performance dimensions so to determine what to measure (Van Dooren et al., 2015).

Performance Dimensions

The discussion on the two perspectives of performance has introduced some fundamental dimensions of performance. Both production and public value models measure the use of resources, quality and cost of processes, quality and volume of outputs, and outcomes achieved by public sector organizations (OECD, 2009). This implies that public organizations need a wide range of measures, such outputs, efficiency, outcomes, and effectiveness, to cover the entire extent of performance.

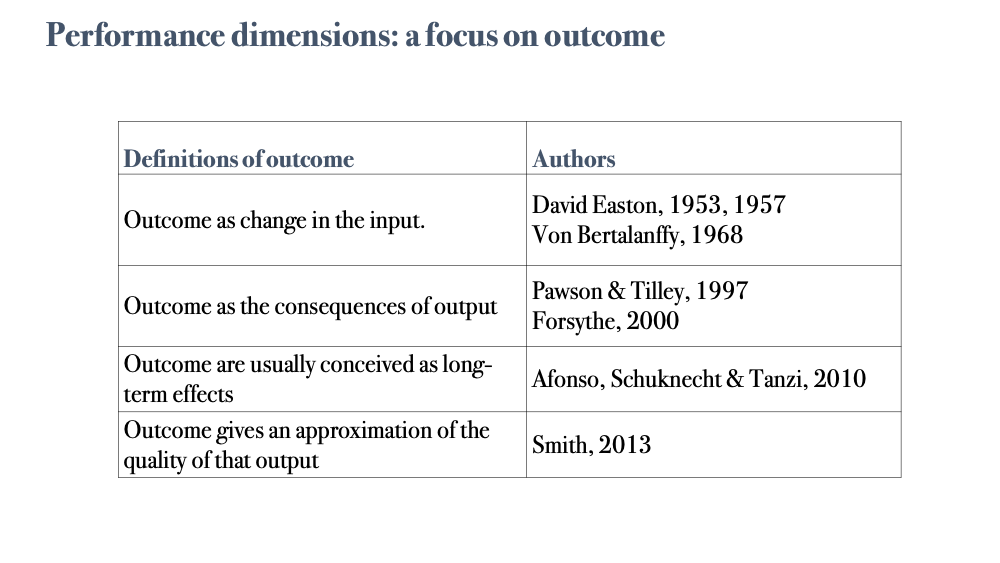

An output configures an immediate result of an activity, for example the issuing of a certificate, the spending of money, the deliveries of a service; an outcome expresses “everything beyond outputs” (Bouckaert & Halligan, 2008a: 16).

The latter can be understood as the effects or the impact that an activity has on the external context. By using the above-mentioned examples: the fraction of certificates issued correctly, what has improved the public spending, and, lastly, the effectiveness of that service delivery. The measurement of an outcome implies an estimation of the worth of what has been delivered by public sector organizations, it proxies the quality of a quantitative output or a volume. “Such a view implies the existence of an identity of the form: Outcome = Valuation (output * quality)” (Smith, 2013, p. 2).

Other key dimensions refer to the internal efficiency that measures the ability of an agency in “turning inputs into outputs” (Talbot, 2009: 499) and it can be associated at the maximum production yield of an organization when operating along its production frontier (Van Dooren et al., 2015). On the other side, the allocative efficiency allows organizations to understand the effect of resources’ allocation to a specific policy area. As Schick (1996: 87) argued, the “efficiency in producing outputs is not the whole of public management. It also is essential that government has the capacity to achieve larger political and strategic objectives. […] It will have to move from management issues to policy objectives, to fostering outcomes.” The ratio between output and outcome can be used as a measure of effectiveness (Bouckaert & Halligan, 2008a). In the same way, the comparison of inputs vs. outcomes focuses on the organizational capacity to address societal requests expressed within the political system.

Levels of performance

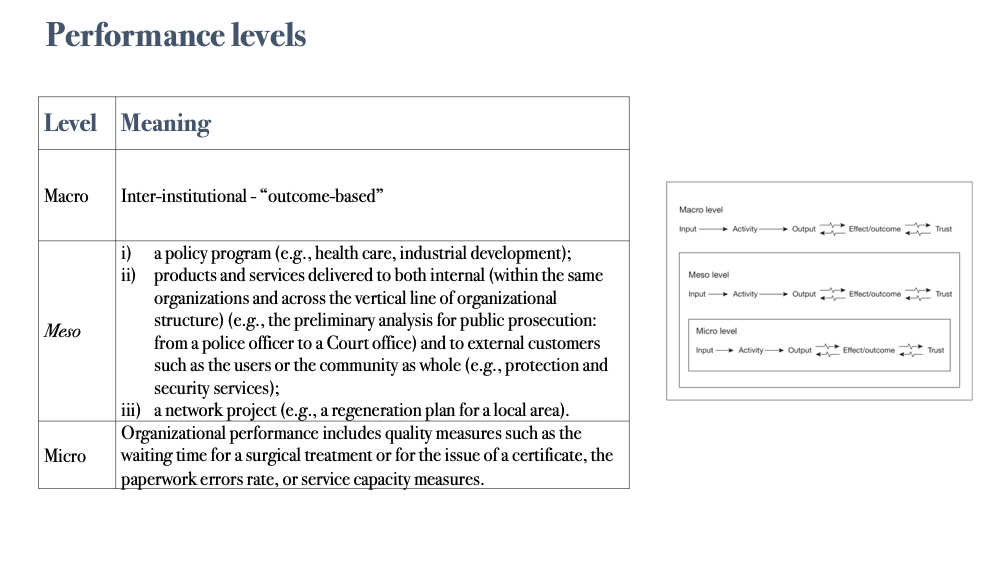

Performance can be framed under three main “levels” of analysis (Bianchi, 2010; Bouckaert & Halligan, 2008a): (i) a political (or macro level); (ii) a managerial (or micro level); and (iii) a political vs. managerial conversation (or meso level).

The first level refers to the national/international scale (i.e., macro level) and implies gauging four types of results (Fukuyama, 2013): i) procedural measures (corruption, tax evasion, gender discrimination at workplace); ii) capacity measures (taxation, education of public service employee and professionalization); iii) output/outcome measure (education scores, GDP, literacy, public health, public security and national defense); and iv) bureaucratic autonomy measures (as a response to-principal agent theory implications). These empirical measures are examples through which assess and compare the quality of public sector services. However, data may not cover all of these areas making them difficult to measure. Furthermore, main issues regarding the national scale concern the conceptualization behind such performance measurements (Fukuyama, 2013). A macro perspective of performance can also be seen, for instance, as the case of a local area that needs to align its strategies with few involved Municipalities. One may call this perspective “inter-institutional” (Bianchi, 2010: 376; Borgonovi, Rivenbark, & Bianchi, 2014; Marques, Ribeiro, & Scapens, 2011; Ongaro, 2015), “governance wide” (Bouckaert & Halligan, 2008a: 18), or “outcome-based” (Bianchi, 2015; Borgonovi, Anessi-Pessina, & Bianchi, 2018).

At a micro level of analysis, the concept of performance is mainly associated with organizational results such as the volume of services or products delivered by a public organization to the community. Although, organizational performance is customer-focused and expresses the efficiency in the allocation of outputs, the quality of deliveries and the customer service level are also considered (Talbot, 2009: 498). Indeed, organizational performance includes quality measures such as the waiting time for a surgical treatment or for the issue of a certificate, the paperwork errors rate, or service capacity measures. These dimensions may pertain to a unit, a department or a group of those and give substance and meaning to organizational performance.

Meso level analysis refers to three main areas of application (Van Dooren et al., 2015): i) a policy program (e.g., health care, industrial development); ii) a value chain leading to products and services delivered to both internal (within the same organizations and across the vertical line of organizational structure) (e.g., the preliminary analysis for public prosecution: from a police officer to a Court office) and to external customers such as the users or the community as whole (e.g., protection and security services); iii) a network project (e.g., a strategic plan for a destination).

At this level of analysis, performance is primarily meant as intermediate (e.g., trust within the network, the quality of partner agreement, the capacity of an healt care network) and final outcomes (e.g., the quality of life in a place, the image, the quality of a service). Meso level results are attained by the networked organizations committed to address a specific policy field (e.g., high specialized health care treatments, crime prevention, mobility, education, unemployment). Thereby, performance management system must connect the outputs that each organization involved in such a network produced, with both intermediate and final outcomes achieved through the implemented policy at meso level (Bouckaert & Halligan, 2008a).

Incorporation of performance

Managing performance requires measurement, but also incorporation of performance information into management and policy system (Bouckaert & Halligan, 2008a). In other words, measurement produces information that needs to be integrated into management systems before it can be utilized.

Incorporation and use have been distinguished. Beyer & Trice (1982) have argued that the use of knowledge (i.e., performance information) is a two-stage behavioral process: adoption and implementation. The first refers to the development of a capacity to act, here intended as “the development of measures of outputs, outcomes, and efficiency” (Julnes & Holzer, 2001: 695), while the second represents knowledge converted into action (Stehr, 1992). From such a distinction it emerges that incorporation and use – namely adoption and implementation – can vary across organizations. For instance, an organization can have good performance tools (e.g., budgets, scorecards, benchmarks), though these are not used as source for decision-making.

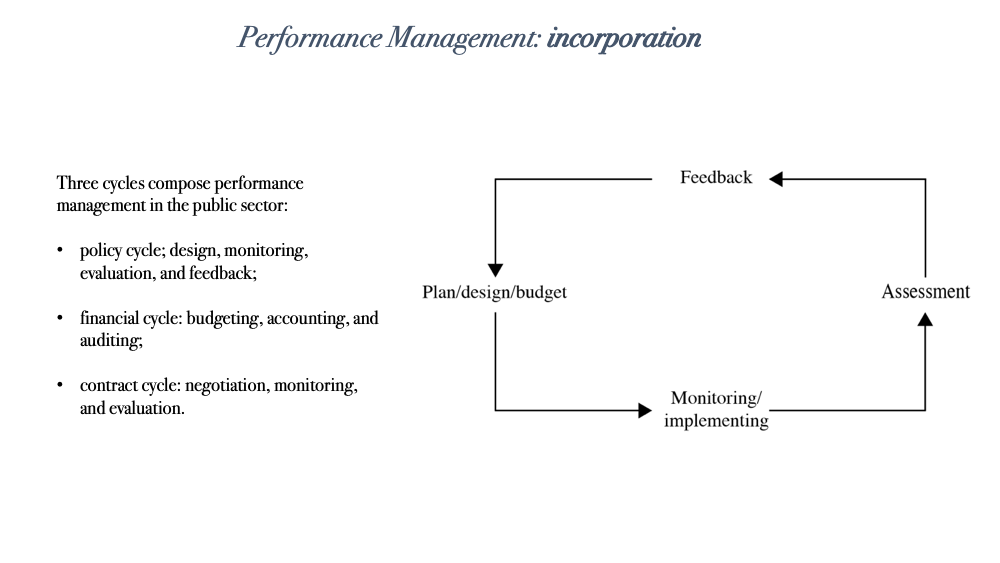

Three cycles compose performance management in the public sector:

- policy cycle; design, monitoring, evaluation, and feedback;

- financial cycle: budgeting, accounting, and auditing;

- contract cycle: negotiation, monitoring, and evaluation.

Policies defines priorities and allocate resources for addressing issues through specific budgets. which identifies and select certain service strategies by the means of contracts (Rebora & Meneguzzo, 1990). Policies are monitored, budgets are accounted, and contract entails implementation of agreements. To this phase an evaluation stage follows that provide the feedback for the next cycle to occur.

Incorporation means therefore the adoption of performance information within these cycles. “By incorporating performance information, the capacity of organizations to control their goal attainment should be enhanced. In this sense, incorporation is a bridge between measurement and use” (Van Dooren et al., 2015, p. 113).

Using information to manage performance

Within both policy and management cycles the use of performance information can have different purposes. The way in which public agencies make use of these information has been recognized as a “pressing challenge” (Moynihan & Pandey, 2010: 849) for public management scholars. A selective and smart use of information may enhance performance management systems. Such an ability depends on the factors enabling its use, as well as on the extent to which public managers make use of them.

Performance measurement can become an end per se (Vakkuri & Meklin, 2006), unless the information it produces may support the management (de Lancer Julnes & Holzer, 2001) of budgets, human resources, and contracts (Miller, Hildreth, & Rabin, 2001), as well as for reporting results. Van Dooren et al. (2015, p. 120) distinguished three main uses of performance information:

- “learning”;

- “steering & improving”; and

- “accountability”.

The first purpose has a future orientation and focuses on errors and faults through the use of learning forums (Moynihan, 2005). Steering & improving has both a present orientation and a future prospect. It includes scorecards aimed at monitoring results and track gaps in performance achievement. Lastly, the use of performance information for accountability aims at clarifying past achievements to different hierarchical levels and audiences: a response to internal need (e.g., executives and political leaders), and external pressure (e.g., politics, citizens, and market) (Bowerman, 1995).

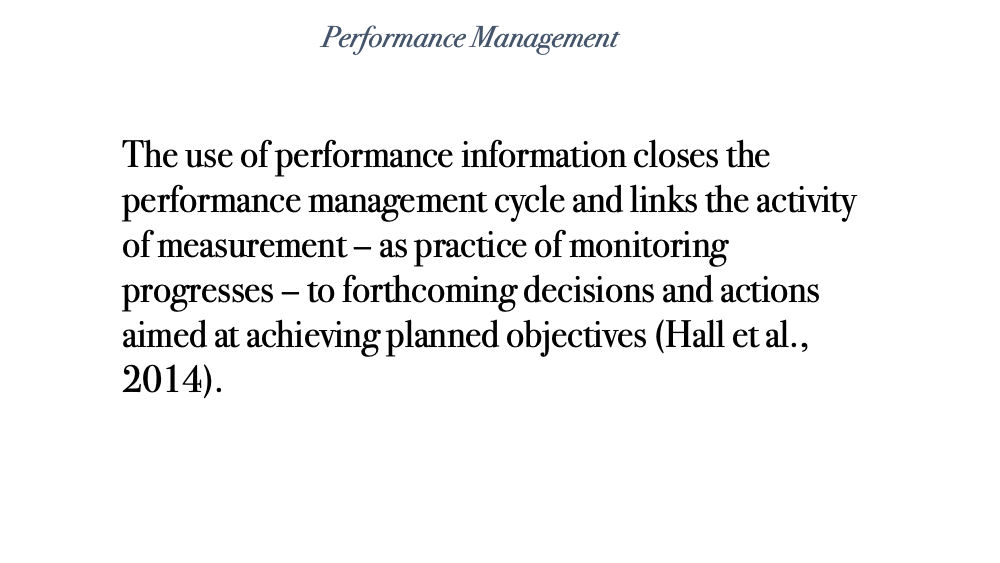

The use of performance information closes the performance management cycle and links the activity of measurement – as practice of monitoring progresses – to forthcoming decisions and actions aimed at achieving planned objectives (Hall et al., 2014). The purpose for the use of performance information has several implications for performance management. To mention the relevant, a correct utilization of measures and associated meanings, the methods to analyze discrepancies, the quality of measurement, and the risk of generating dysfunctional effects. Within the cycle of performance management, the use of information may produce both effective and dysfunctional effects.

Managing performance: towards a performance governance in the public domain

Performance management has changed over time. Innovations and evolutions in both theory and practice of governing public sector achievements have been the result of different performance movements (Halligan, 2007; Radin, 2006). The evolution of performance management in the public sphere has been investigated by several authors.

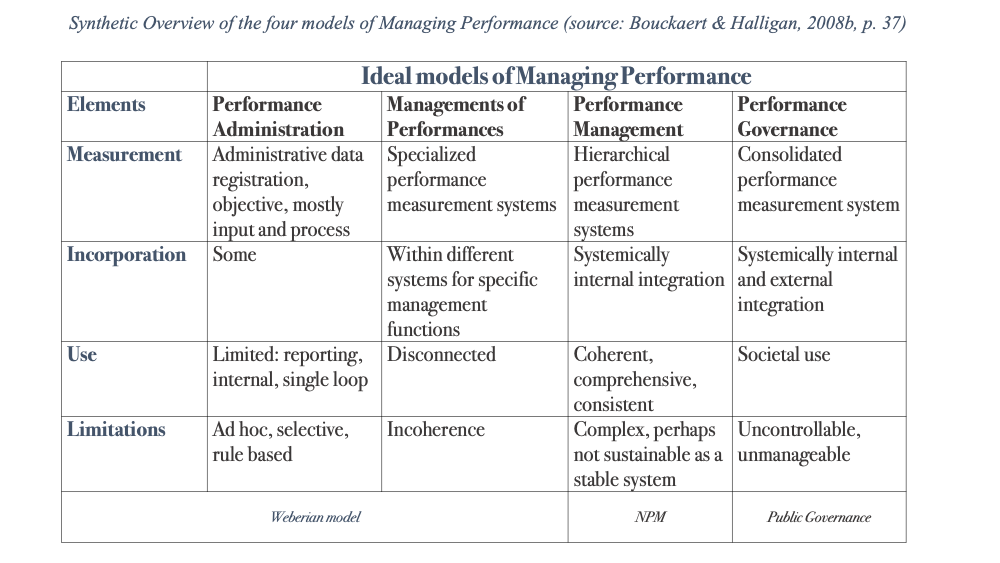

Bouckaert & Halligan (2008) distinguished “between different levels of consolidation and integration of measurement, incorporation and use of performance” (Halligan, Sarrico, & Rhodes, 2012: 225), resulting in four variations of managing performance. These performance regimes (Talbot, 2010) applied by public sector organizations vary across different span and depth of performance: the first element profiles the substance of performance from measuring inputs, to outputs, outcomes, and trust; the second dimension frames the object of management which span from an intra-organizational view (micro), to across organizations within a function or a policy theme (meso), to across the whole-of-government (macro). The relations between these components configure four approaches to managing performance: “Performance Administration, Managements of Performances, Performance Management, and Performance Governance” (Bouckaert & Halligan, 2008a: 32).

The four models of managing performance can be used to explain the evolution of performance management over the years and the relations among its components – measurement, incorporation, and use (Bouckaert & Halligan, 2008b). Therefore, these four models are described through the logical sequence of the performance management practice: collecting, converting data into information available to the management for them to use into decision-making processes, and for accountability purposes (e.g., external reports, data warehouse).

The first model has been called Performance Administration. Its elements profile a Weberian view of managing performance. The model shows a certain tension to measurement, though centered on input and processes with limited focus on achievements. This narrow focus implies that performance is registered and administered through rules and procedure prescribed by laws. It counts on scientific management principles within hierarchical chain of command. Measurement is based on a linear input/output model with a focus on productivity and technical efficiency (Bouckaert, 1990; Holzer et al., 2009; Ridley & Simon, 1943). The incorporation of performance information in policy and management cycle is narrow with a partial impact on decision making processes. Performance information use is limited to administrative accountability purposes. The system is static and the control is focused on micro organizational behavior.

Managements of Performance is an advancement of the Weberian view. Indeed, the measurement of performance is associated with several management functions, though it shows disjunctions among indicators and lack of system’s integration and consistency in policy design and management. Due to its focus on both structures and functions of management, there is an interactive measurement process – termed as “situational assessment” (Sink, Tuttle, & Devries, 1984: 266) – within each management function. This process is influenced by the ability to measure outputs, and those conditions determining the possibility to measure behavior and output (Ouchi, 1979: 843). In other words, measurement becomes an instrument to change behavior of individuals. The shift from performance administration to managements of performance linked the measurement of inputs with outputs (Atkinson, 2005), rather than using the former as measure of results. Furthermore, it challenged measures of productivity and efficiency with a variety of governmental outputs and dimensions of quality (Hatry, 1977; Hjerppe & Luoma, 1997). In this type of managing performance, the use of performance information is limited within the boundaries of different department/function (Ferlie, Lynn, & Pollitt, 2005), sometimes in the absence of a coordination mechanisms, other with a limited top-down guided innovation in performance management practice.

A third model of managing performance has emerged as an improvement of Managements of Performance. Some of the previous shortcomings were tackled. The model of Performance Management encompasses measurement, incorporation, and use of performance information with the intent to improve organizational results. Usually, it configures a system and include tools and practices to manage the achievement of results. A Performance Management-inspired application indicates an effort towards the design of integrated system. However, this model has shown its limitations within the dynamic and complex environment (OECD, 2017) that characterizes public sector challenges (e.g., crime, pollution, unemployment, urban growth, mobility).

To cope with limitation of traditional and narrow approaches to performance management in the public sector, in the recent years a fourth model has been envisaged. This innovative mode comprises a full range version of span and depth of performance. Particularly this model, termed as Performance Governance, is attracting a “growing research interest” (Halligan, 2006; Hawke, 2012; Talbot, 2010) with emphasis on cross-agency, cross-sectoral, and multilevel programs or policies, rather than on the individual agency. It is known as whole-of-government (Christensen & Lægreid, 2007a), collaborative governance (Ansell & Gash, 2007; Emerson, Nabatchi, & Balogh, 2012), integrative leadership, public value governance, and cross-sectoral collaboration (Bryson, Crosby, & Bloomberg, 2014; Crosby & Bryson, 2010). The interest is twofold. On one side, on the role (e.g., leadership, coordination, and control) that an organization can play in leading the development a local area (macro), implementing a public policy (meso) or delivering of a service (micro) (Christensen & Lægreid, 2007b), and, on the contextual conditions that nurture such processes, on the other.

Indeed, there are evidence that reforms in some nations (e.g., Australia, New Zeland, United Kingdom) attempted to align systemic elements and public ends with the use of “horizontally-integrated, whole-of-government capacity and capability” (Boston & Eichbaum, 2005: 34), so to reduce hierarchy and fragmentation.

Connecting governance with performance means expanding the domain of performance management in the public sector well beyond the traditional perspective of administering public sector achievements, as merely the result of a “black box”. This emerging approach combines different streams of thoughts which brings together governance and performance. A certain tension for measuring government-wide performance (Bouckaert & Halligan, 2008a; OECD, 2009) is extensively recognized within public management literature, and it has been recently acknowledged:

- the relevance of private sector’s managerialism into the public realm (Farnham & Horton, 1993; Pollitt, 1990);

- the acceptance that policy-making is conceived as an interplay between actors, implying a full-extent search for new piloting methods and strategy (Kooiman, 1993; Rhodes, 1996);

- the applicability of network theory to public sector issues and the capacity of government to play a leading role in pursuing public interests (Klijn & Koppenjan, 2000; Mandell & Keast, 2008);

- the belief that managing performance requires an understanding of the key relationships between stakeholders (Agranoff & McGuire, 2003);

- the wish to smooth inconsistencies between different policies, combined with the aim to increase their effectiveness through “joined-up government” (Pollitt, 2003), whole-of-government (Christensen & Lægreid, 2007a), and horizontal management (Sproule-Jones, 2000) approaches;

- the obsolescence of traditional modes of service planning, management and delivery of public services (Bovaird, 2007);

- the raise of a movement that goes beyond traditional public administration and aims to offer a response “to the challenges of a networked, multi-sector, no-one-wholly-in-charge world and to the shortcomings of previous public administration approaches” (Bryson et al., 2014).

- the bearing of a new “public service logic” that differentiate a product dominant conception of co-production of value from a co-creation of value out of a nexus of interactions (Osborne, 2018; Osborne, Radnor, & Nasi, 2012).

Form these propositions, it emerges that the substance of performance crosses organizational boundaries, thereby implying collaboration in policy design and implementation through a net of stakeholders. The achievement of public purposes entails prompting methods to foster citizens participation and community involvement into the delivery of public services. Accountability and performance assessment require differentiated strategies for targeted audience (e.g., “exit” and “voice” mechanisms). The architecture of performance management systems is crucial to well-balance managerial values, political priorities, and the institutional setting (Borgonovi, 2002). This system should be able to measure and monitor the results of multilevel programs (i.e., micro, meso, and macro) and capture their impacts on society (i.e., outcomes).

Ultimate public ends have nothing to do with outputs. An output of a public agency is a means to enable someone to achieve something else. For instance, a construction permit is an output provided to citizens and construction firms in order to build up houses and apartments. Communities recognize as part of the mission of a municipality to allow them to construct and to ensure people to have a house.

The number of people who had a surgery treatment in a year is a result of a public hospital measured in term of output volume. The number of people who are still alive five years after a liver transplant – when compared to that output – is a measure of outcome. The value of outcome indicators is influenced not only by the quality of the output provided by the public hospital five years before, but it is also influenced by other stakeholders (e.g., family of the patient and local health care device). Therefore, when considering public ends, performance pertain – at least – to the level of a policy field (Bouckaert & Halligan, 2008a: 16).

The focus on outcomes connects Public Governance with performance management of public sector organizations. A wide perspective that emphasizes the need of measuring outcomes and to considering how the coordination of different organizations impacts on the achievement of public ends. This is a progress that faces the limitations of technical efficiency measures by integrating them with allocative efficiency measures (Boyne, 2002: 17–19).

In addition to traditional domains of performance, such as outputs and efficiency. A local government must include other dimensions. Service outcomes indicators measure the ability of an organization to impact on the service user (e.g., the change in the number of patients effectively recovered from illness through cares, the change in the graduate students which belong to the lower income brackets). Responsiveness grasps the ability of the system to provide on-time, appropriate, and effective responses to citizens’ needs (e.g., the average waiting time for a surgery treatment, capacity to evacuate people in order to rescue them from an earthquake). Lastly, Public Governance implies that democratic values are considered (Sørensen & Torfing, 2007). Indeed, these measures address specifically the publicness (e.g., the change in the number of citizens who participate in forum about public issues, accountability measures) of the ends.

Spanning the boundaries of Performance Management in the public sector: from single organization focus towards an interinstitutional perspective

In order to span the boundaries from single organization towards multi-organizational settings it is required to:

- put more emphasis on policy understanding – why certain outcomes have been achieved while others lag behind, i.e. enhancing policy and organizational learning;

- assess how social and inter-organizational networks shape beliefs, policies and outcomes;

- widen the time horizon from one year up to 5–10 years; and

- replace rigid strategies with flexible scenarios that better consider weak signals, tacit information and alternative policy options.

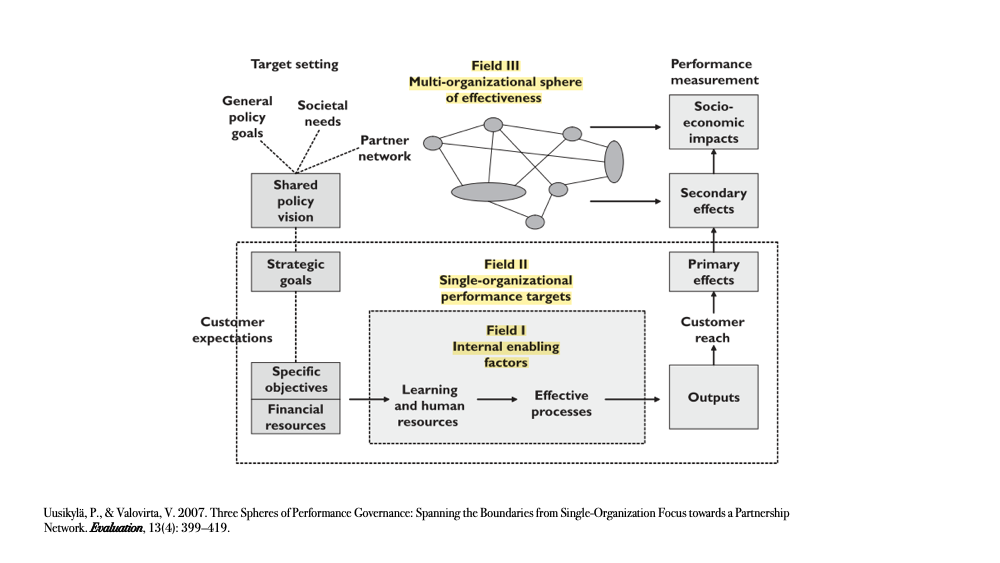

What is needed is a shared policy vision that reflects the more general policy goals, societal needs and the division of responsibilities between the different actors in the partner network. From these strategic goals the more specific objectives for single organizations can be derived. Also, operationalized equivalent of the goals and objectives, namely the intervention logic upon which the performance measurement should be based.

In the multi-organizational sphere of effectiveness, the target setting should take place as strategic discussion and involve a relevant collection of actors – public, semi-public and non-governmental. The strategy formulation can be greatly facilitated by cognitive mapping of the strategic intent. It should result in persuasive policy visions as well as a clear division of responsibilities between the partners.

Levels of performance

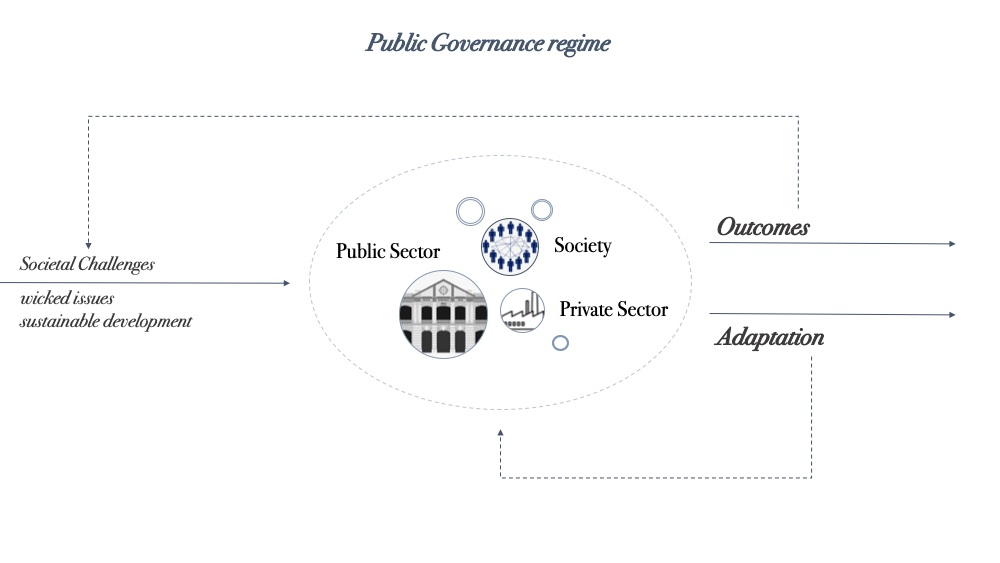

Collaborative Governance regimes generate outputs (or collaborative actions) that are intended to produce outcomes that in turn may lead to adaptation.

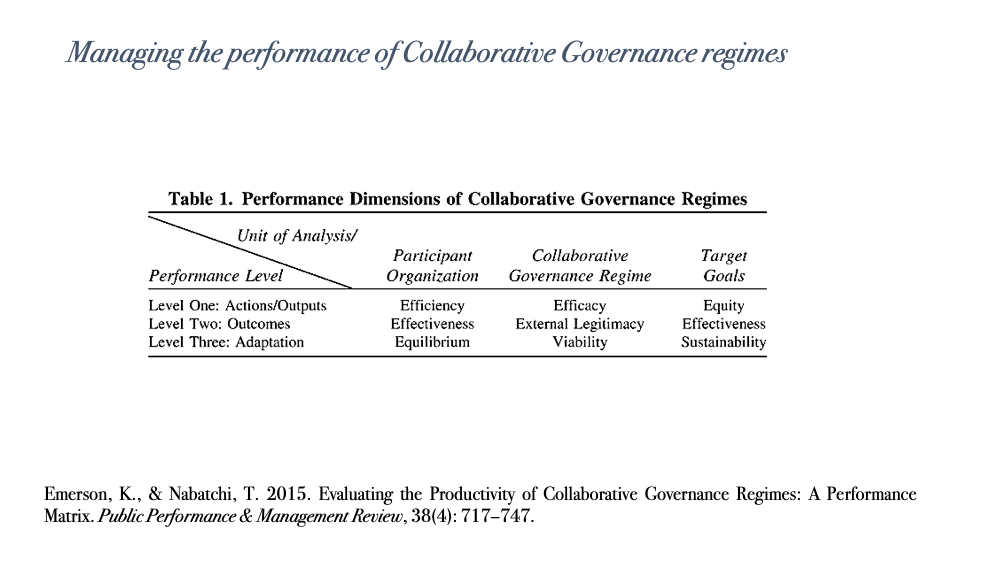

Managing the performance of Collaborative Governance regimes includes assessing three levels. In assessing the productivity performance of CGRs, one could evaluate any of the three performance levels (actions, outcomes, and adaptation) at any of the three units of analysis (participant organizations, CGR, and target goals).

Collaborative actions (outputs)

People and organizations collaborate across boundaries to get something done. Thus, collaborative governance is intended to be instrumental, propelling actions or outputs that “could not have been attained by any of the organizations acting alone” (Huxham, Vangen, Huxham, & Eden, 2000). These may include securing endorsements, educating constituents or the public, enacting policy measures (new laws or regulations), marshaling external resources, deploying staff, siting and permitting facilities, building or cleaning up, carrying out new management practices, monitoring implementation, or enforcing compliance.

Outcomes

Intended outcomes are of the greatest interest to evaluators, but unintended consequences should also be considered. They can be physical, environmental, social, economic, and/or political. They can be short-lived or long-term, very specific or quite broad in their reach, and/or discrete or cumulative in nature. The less proximate outcomes are to the collaborative action or the more dependent they are on other contributing or intervening factors, the more difficult it is to attribute the specific outcomes directly to collaborative efforts.

Adaptations

This potential for transformative change is the foundation for the concept of adaptation, which can be understood as adaptive responses to the outcomes of collaborative actions. Adaptation is also a central concept in the adaptive resource management literature, which calls for the reduction of uncertainty over time through system monitoring and the improvement of long-term outcomes through learning.

Unit of analysis

Like networks, which “must contend with the joint-production problem of multiple agencies producing one or more pieces of a single service”. This cross-boundary work inherently involves tensions, such as “reduced autonomy, shared resources, and increased dependence” (Provan & Milward, 2001).

Participant Organizations

For example, organizations may be motivated to participate in a CGR by the desire to adhere to a legal or administrative command (as in mandated collaboration), or by an interest in reputational benefits, or by a stake in resolving a costly conflict or producing a collective good.

The CGR

This system-based performance approach is central to the study of public management networks.

Target Goals (meso i.e. policy field level)

The target goals that the CGR is trying to accomplish with respect to the public problem, condition, service, or resource being addressed. Within each of these focal areas, CGRs might aim to improve, expand, or limit these resources and services through collaborative actions.

Combining three performance levels (actions, outcomes, and adaptation) with the three units of analysis (participant organizations, CGR, and target goals) several performance dimensions emerge.

PRODUCTIVITY AT INDIVIDUAL ORGANIZATION

Efficiency of actions/outputs. For participant organizations, the performance of CGR actions may be assessed by the efficiencies they create for individual organizational operations. Improved coordination through the CGR may reduce the information costs for organizations and enable more efficient operations with fewer redundancies among members.

Effectiveness of outcomes. CGR actions will generate intermediate and end outcomes. Measures of participant satisfaction are often used as an indirect measure of collaborative effectiveness, on the assumption that were participants not achieving their own self-interests, they would not attribute any gains to the CGR.

Equilibrium of adaptation. CGRs are created in response to some condition or demand in the external system context that individual organizations cannot respond to adequately on their own. How well participating organizations manage to adapt, and at the same time remain sufficiently stable to perform their missions, is a central challenge in collaborative governance.

PRODUCTIVITY AT THE CGR

Efficacy of actions/outputs. Efficacy is the most salient performance dimension of actions or outputs at the CGR unit of analysis. Efficacy refers to the capacity of the actions to produce effects that are consistent and aligned with the shared expectations, prior agreements, and strategy for accomplishing the CGR’s purpose.

Legitimacy of outcomes. Legitimacy and legitimacy-building are long-studied concepts within organizational development and more recently within the study of interorganizational networks. In assessing productivity performance, we consider the external perception of legitimacy as a critical outcome for CGRs to continue to produce over time. The CGR must obtain sufficient reputational benefits from being perceived as viable by relevant external funders, leaders, or publics, and concomitantly by attracting needed external resources and support.

Viability of adaptation. As a CGR system-level performance measure of adaptation, viability provides confirmation that the CGR has the continuing capacityto add value above and beyond individual participant efforts.

PRODUCTIVITY AT THE TARGET GOALS UNIT OF ANALYSIS

Equity of actions/outputs. Organizations work together in situations where competition or governmental fiat has not succeeded previously or is not appropriate or possible.

Effectiveness of outcomes. Effectiveness is the primary performance dimension for outcomes at the target goals unit of analysis, namely the extent to which the desired change in the targeted public condition, good, service, or product is achieved.

Sustainability of adaptation. Sustainability is a signal performance dimension for adaptation at the target goals unit of analysis. By sustainability, we mean both the robustness and the resilience of the adaptive responses to outcomes on the targeted resource or service condition, given the uncertain and changing external context, influences, and events.

In sum, a comprehensive assessment of the productivity performance of CGRs requires an examination of three performance levels (actions, outcomes, and adaptation) at three units of analysis (participant organizations, the CGR itself, and target goals). These levels and units of analysis create an analytical space for nine salient dimensions of CGR performance.

Conclusion

With the rise of public governance paradigm, the scope of public administration has been extended towards an inter-organizational focus of public policy design and management. A clear sign was the identification of outcome of policies as a main concern for government and the belief that the private sector is no more meant as an alternative to the public. Spanning the boundaries of performance management in the public sector is intended to bring together ideas from the literature of both policy studies and research on management and organization. It is an attempt to move towards greater recognition of the distinctive features of public policy management and governance.

In this perspective, additional features of policy design and implementation have to be considered. This refers to the inter-institutional nature of public governance and the challenges it poses to performance management in term of measurement, incorporation and use of performance information. To conclude, managing performance of networks, particularly when these are collaborative, widens the span and depth of performance well-beyond policy outputs. Main results to be considered are outcomes and adaptations as source of performance sustainability, particularly for policy networks and collaborative regimes.

Refrences

Agranoff, R., & McGuire, M. 2003. Collaborative Public Management. New Strategies for Local Governments. Washington, USA: Georgetown University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2tt2nq.

Ansell, C., & Gash, A. 2007. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(4): 543–571.

Atkinson, A. B. 2005. The Atkinson review: final report. Measurement of government output and productivity for the national accounts. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

Beyer, J. M., & Trice, H. M. 1982. The Utilization Process : A Conceptual Framework and Synthesis of Empirical Findings Author ( s ): Janice M . Beyer and Harrison M . Trice Published by : Sage Publications , Inc . on behalf of the Johnson Graduate School of Management , Cornell University. Administrative Science Quarterly, 27(4): 591–622.

Bianchi, C. 2010. Improving performance and fostering accountability in the public sector through system dynamics modelling: From an ‘external’ to an ‘internal’ perspective. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 27(4): 361–384.

Bianchi, C. 2015. Enhancing Joined-Up Government and Outcome-Based Performance Management through System Dynamics Modelling to Deal with Wicked Problems: the Case of Societal Ageing. Systems Research & Behavioural Science, 32: 502–505.

Borgonovi, E. 2002. Principi e sistemi aziendali per le amministrazioni pubbliche. Milano: EGEA. https://books.google.it/books?id=ADM5AAAACAAJ.

Borgonovi, E., Anessi-Pessina, E., & Bianchi, C. 2018. Outcome-Based Performance Management in the Public Sector. Cham, Zurich: Springer.

Borgonovi, E., Rivenbark, W. C., & Bianchi, C. 2014. Introduction to a Symposium on Broadening the Application of Performance Management. International Journal of Public Administration, 37(13): 909–910.

Boston, J., & Eichbaum, C. 2005. State Sector Reform and Renewal in New Zealand: Lessons for Governance. Paper prepared for the Conference on Repositioning of Public Governance – Global Experiences and Challenges. Taipei, 18–19 November.

Bouckaert, G. 1990. The History of the Productivity Movement. Public Productivity & Management Review, 14(1): 53.

Bouckaert, G., & Halligan, J. 2008a. Managing performance: International comparisons. London: Routledge.

Bouckaert, G., & Halligan, J. 2008b. Comparing Performance across Public Sectors. In W. Van Dooren & S. Van de Walle (Eds.), Performance Information in the Public Sector: How it is Used: 72–93. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Bouckaert, G., Van de Walle, S., & Kampen, J. K. 2005. Potential for comparative public opinion research in public administration. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 71(2): 229–240.

Bovaird, T. 2007. Beyond engagement and participation: User and community coproduction of public services. Public Administration Review, 67(5): 846–860.

Bovaird, T. 2008. Political Economy Perspectives on Performance Measurement. In R. Thorpe & J. Holloway (Eds.), Performance Management: Multidisciplinary Perspectives: 184–199. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Bovaird, T., & Löffler, E. 2003. Evaluating the quality of public governance: indicators, models and methodologies. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 69(3): 313–328.

Bowerman, M. 1995. Auditing Performance Indicators: the Role of the Audit Commission in the Citizen’S Charter Initiative. Financial Accountability and Management, 11(2): 171–183.

Boyne, G. A. 2002. Theme: Local Government: concepts and indicators of local authority performance: an evaluation of the statutory frameworks in England and Wales. Public Money and Management, 22(2): 17–24.

Boyne, G. A., Meier, K. J., O’Toole, L. J., & Walker, R. M. 2006. Public service performance: Perspectives on measurement and management. Public Service Performance: Perspectives on Measurement and Management. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511488511.

Bryson, J. M., Crosby, B. C., & Bloomberg, L. 2014. Public value governance: Moving beyond traditional public administration and the new public management. Public Administration Review. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12238.

Cepiku, D. 2016. Performance Management in Public Administration. In T. Klassen, D. Cepiku, & T. J. Lah (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Global Public Policy and Administration. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Christensen, T., & Lægreid, P. 2007a. The whole‐of‐government approach to public sector reform. Public Administration Review, 67(6): 1059–1066.

Christensen, T., & Lægreid, P. 2007b. Transcending New Public Management: The Transformation of Public Sector Reforms. Ashgate. https://books.google.it/books?id=3wzM4x-Ax5IC.

Christensen, T., & Lægreid, P. 2010. Increased complexity in public organizations—the challenges of combining NPM and post-NPM. In P. Lægreid & K. Verhoest (Eds.), Governance of public sector organizations: 255–275. Springer.

Crosby, B. C., & Bryson, J. M. 2010. Integrative leadership and the creation and maintenance of cross-sector collaborations. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(2): 211–230.

de Lancer Julnes, P., & Holzer, M. 2001. Promoting the Utilization of Performance Measures in Public Organizations: An Empirical Study of Factors Affecting Adoption and Implementation. Public Administration Review, 61(6): 693–708.

Dubnick, M. 2005. Accountability and the Promise of Performance: In Search of the Mechanisms. Public Performance & Management Review, 28(3): 376–417.

Emerson, K., Nabatchi, T., & Balogh, S. 2012. An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 22(1): 1–29.

Farnham, D., & Horton, S. 1993. The new public service managerialism: an assessment. Managing the new public services. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan.

Ferlie, E., Lynn, L., & Pollitt, C. 2005. The Oxford Handbook of Public Management. Oxford University Press. https://books.google.it/books?id=_0epYa1LF8MC.

Fukuyama, F. 2013. What is governance? Governance, 26(3): 347–368.

Halligan, J. 2006. The Reassertion of the Centre in a First Generation NPM System. In T. Christensen & P. Lægreid (Eds.), Autonomy and Regulation. Coping with Agencies in the Modern State: 162–180. UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Halligan, J. 2007. Reform Design and Performance in Australia and New Zealand. In T. Christensen & P. Lægreid (Eds.), Transcending New Public Management.The Transformation of Public Sector Reforms: 43–64. London: Routledge.

Halligan, J. 2010. Post-NPM responses to disaggregation through coordinating horizontally and integrating governance. In P. Lægreid & K. Verhoest (Eds.), Governance of public sector organizations: 235–254. Springer.

Halligan, J., Sarrico, C., & Rhodes, M. L. 2012. On the road to performance governance in the public domain? International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 61(3): 224–234.

Hatry, H. P. 1977. How effective are your community services?: Procedures for monitoring the effectiveness of municipal services. Urban Institute.

Hawke, L. 2012. Australian public sector performance management: Success or stagnation? International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 61(3): 310–328.

Hjerppe, R., & Luoma, K. 1997. Finnish Experiences in Measuring and Promoting Productivity in the Public Sector. VATT Institute for Economic Research.

Holzer, M., Fry, J., Charbonneau, E., Riccucci, N., Kwak, S., et al. 2009. Literature Review and Analysis Related to Measurement of Local Government Efficiency.

Hood, C. 1991. A Public Management for All Seasons? Public Administration, 69(1): 3–19.

Huxham, Chris, Vangen, S., Huxham, C, & Eden, C. 2000. The Challenge of Collaborative Governance. Public Management: An International Journal of Research and Theory, 2(3): 337–358.

Imperial, T. 2005. Collaboration and performance measurement: lessons from three watershed governance efforts. In J. M. Kamensky & A. Morales (Eds.), Managing for Results: 379–424. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Julnes, P. de L., & Holzer, M. 2001. Promoting the Utilization of Performance Measures in Public Organizations: An Empirical Study of Factors Affecting Adoption and Implementation. Public Administration Review, 61(6): 693–708.

Klijn, E. H., & Koppenjan, J. F. M. 2000. Public Management and Policy Networks. Public Management: An International Journal of Research and Theory. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030000000007.

Kooiman, J. 1993. Modern governance: new government-society interactions. London: Sage.

Mandell, M. P., & Keast, R. 2008. Evaluating the effectiveness of interorganizational relations through networks. Public Management Review, 10(6): 715–731.

Marques, L., Ribeiro, J. A., & Scapens, R. W. 2011. The use of management control mechanisms by public organizations with a network coordination role: A case study in the port industry. Management Accounting Research, 22(4): 269–291.

Miller, G., Hildreth, B., & Rabin, J. 2001. Performance Based Budgeting. Boulder: CO: Westview.

Moore, M. H. 1995. Creating Public Value: Strategic Management in Government. Harvard University Press. https://books.google.it/books?id=Hm9uKVj0qDYC.

Moore, M. H. 2013. Recognizing Public Value. Harvard University Press. https://books.google.it/books?id=Lnil7UXE-4IC.

Moore, M. H., & Hartley, J. 2008. Innovations in governance. Public Management Review, 10(1): 3–20.

Moynihan, D. P. 2005. Goal-based learning and the future of performance management. Public Administration Review, 65(2): 203–216.

Moynihan, D. P. 2008. The Dynamics of Performance Management. Georgetown University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2tt51c.

Moynihan, D. P., & Pandey, S. K. 2010. The Big Question for Performance Management: Why Do Managers Use Performance Information? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 20(4): 849–866.

OECD. 2009. Measuring Government Activity. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. 2017. Systems Approaches to Public Sector Challenges. OECD Publishing. file:///content/book/9789264279865-en.

Ongaro, E. 2015. Multi-level governance: The missing linkages. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Osborne, S. 2006. The new public governance? Public Management Review, 8(3): 377–387.

Osborne, S. 2018. From public service-dominant logic to public service logic: are public service organizations capable of co-production and value co-creation? Public Management Review, 20(2): 225–231.

Osborne, S., Radnor, Z., & Nasi, G. 2012. A New Theory for Public Service Management? Toward a (Public) Service-Dominant Approach. The American Review of Public Administration, 43(2): 135–158.

Ouchi, W. G. 1979. A Conceptual Framework for the Design of Organizational Control Mechanisms. Management Science, 25(9): 833–848.

Poister, T. H., Aristigueta, M. P., & Hall, J. L. 2014. Managing and Measuring Performance in Public and Nonprofit Organizations: An Integrated Approach. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Pollitt, C. 1990. Managerialism and the Public Services: The Anglo-American Experience. Cambridge, MA: Basil Blackwell. https://books.google.it/books?id=0oB9QgAACAAJ.

Pollitt, C. 2003. Joined-up Government: A Survey. Political Studies Review, 1(1): 34–49.

Pollitt, C., & Bouckaert, G. 2011. Public Management Reform: A Comparative Analysis. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. https://books.google.it/books?id=E0fdN3KiPmgC.

Provan, K. G., & Milward, H. B. 2001. Do Networks Really Work? A Framework for Evaluating Public-Sector Organizational Networks. Public Administration Review, 61(4): 414–423.

Radin, B. A. 2006. Challenging the performance movement : accountability, complexity, and democratic values. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

Rebora, G., & Meneguzzo, M. 1990. Strategia elle amministrazioni pubbliche. Torino: Utet.

Rhodes, R. A. W. 1996. The New Governance: Governing without Government. Political Studies, 44(4): 652–667.

Ridley, C. E., & Simon, H. A. 1943. Measuring Municipal Activities: A Survey of Suggested Criteria for Appraising Administration. The International City Managers’ Association. https://books.google.it/books?id=R8zRAAAAMAAJ.

Schick, A. 1996. The Spirit of Reform: Managing the New Zealand State Sector in a Time of Change; a Report Prepared for the State Services Commission and the Treasury, New Zealand. State Services Commission.

Sink, D. S., Tuttle, T. C., & Devries, S. J. 1984. Productivity measurement and evaluation: What is available? National Productivity Review, 3(3): 265–287.

Smith, P. 2013. Measuring Outcome In The Public Sector. New York: Taylor & Francis. https://books.google.it/books?id=GazfAQAAQBAJ.

Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J. 2007. Theories of democratic network governance. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Sproule-Jones, M. 2000. Horizontal management: Implementing programs across interdependent organizations. Canadian Public Administration, 43(1): 93–109.

Stehr, N. 1992. Practical Knowledge: Applying the Social Sciences. London: SAGE Publications. https://books.google.it/books?id=qWwfAAAAMAAJ.

Talbot, C. 2009. Performance Management. In E. Ferlie, L. E. Lynn, & C. Pollitt (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of public management. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199226443.003.0022.

Talbot, C. 2010. Theories of Performance Organizational and Service Improvement in the Public Domain. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Vakkuri, J., & Meklin, P. 2006. Ambiguity in Performance Measurement: A Theoretical Approach to Organisational Uses of Performance Measurement. Financial Accountability & …, 22(3): 235–250.

Van de Walle, S., Van Roosbroek, S., & Bouckaert, G. 2008. Trust in the public sector: is there any evidence for a long-term decline? International Review of Administrative Sciences, 74(1): 47–64.

Van Dooren, W. 2008. Nothing New Under the Sun? Change and Continuity in the Twentieth-Century Performance Movements. Performance Information in the Public Sector, vol. 108: 11–23. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Van Dooren, W., Bouckaert, G., & Halligan, J. 2015. Performance management in the public sector. Routledge.

Van Helden, G. J., Johnsen, Å., & Vakkuri, J. 2012. The life-cycle approach to performance management: Implications for public management and evaluation. Evaluation, 18(2): 159–175.

Voets, J., Van Dooren, W., & De Rynck, F. 2008. A Framework for Assessing the Performance of Policy Networks. Public Management Review, 10(6): 773–790.

Walker, R. M., Boyne, G. A., & Brewer, G. A. 2010. Public Management and Performance: Research Directions. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://books.google.it/books?id=YZaDIftNnWoC.